Who is Dante Alighieri?

For Italians, the name Dante is heard as often as Shakespeare is for English speakers. He is a literary giant. A revolutionary in language. A poet of nearly unmatched, extraordinary genius that we mere mortals can only attempt to comprehend.

I first encountered Dante in my English class sophomore year of high school. The class was about the great epics—we read the Iliad, the Odyssey, the Aeneid, and Dante’s Inferno. Out of all of them, I found Inferno to be the most ambitious, imaginative, and, in my opinion, the most eloquently written. (Even taking into account that I was reading an English translation, which can’t begin to capture the beauty of the original Italian).

To understand what this work was, we need to know who Dante Alighieri was and his history leading up to it. He was born in 1265 in Florence, during a period of intense political tension between two factions: the Guelfs and the Ghibellines. The former supported the Holy Roman Emperor, while the latter supported the pope. Florence was a Guelf city, and Dante, an active member in the party. By 1300, the Florentine Guelfs divided into White Guelfs and Black Guelfs. The Whites, which Dante was a part of, were opposed to more papal influence, specifically that of Pope Boniface VIII. The Blacks continued to support the pope.

Dante’s political affiliation ended up being his downfall—yet, at the same time, beneficial to the literary world. By the time of the split in the Guelf party, Dante had achieved prominence as a politician in Florence. He was married, had children, and was well recognized as a poet thanks to his work La Vita Nuova. When the Black Guelfs took power in Florence, Dante was exiled. He roamed around Italian courts, but he never returned to Florence. He doesn’t mention his family in his works, but there is doubt that he ever saw his wife again, though his sons and daughter possibly joined him at some point.

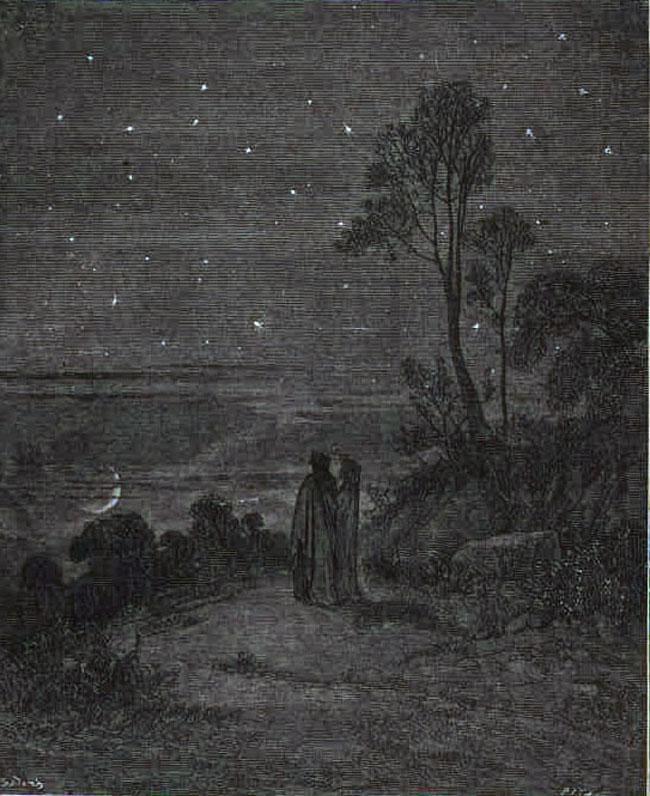

While in exile, he continued writing, producing an “intellectual feast” of political and philosophical musings called Il Convivio, which never gained popularity. Then, around 1308, Dante began the work for which he is best known seven hundred years later: the Commedia. (Divina wasn’t added until the 16th century.) It depicts Dante’s journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven after he “lost the true way,” and is divided into three installments: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso.

The Commedia could be said to be a form of consolation for Dante during his difficult years in exile. In it, he condemns those who are responsible for his current state, dreams of a future in which the world is governed under a single monarch—his idea of perfect harmony—and in which he meets and is guided by those most important and influential to him, including the Ancient Roman poet Virgil, Beatrice, and Cacciaguida.

Beatrice and Cacciaguida are both important in understanding Dante’s other motivations for theCommedia, aside from politics. Beatrice was his ultimate muse. He says to have first met her at the age of nine in this church in Florence:

They only had a few meetings before Beatrice died young—possibly from childbirth—but she was a great source of Dante’s admiration and love, and one of the primary inspirations behind his early poetry in La Vita Nuova. She plays an active role in Paradiso, where she guides Dante through the heavenly spheres. Cacciaguida was an ancestor of Dante’s, a crusader; and though he only appears once in Paradiso, his importance is well established. Dante found consolation from thinking of his ancestry, particularly this heroic figure. However, this reminded him just how unjustly he’d been treated, and backfired on his writing. As Barbara Reynolds points out in her biography on Dante, his anger at those who condemned him threatened to shake the carefully constructed poetry that he otherwise had astounding control upon. At one point, she describes his rage at Boniface as a “monomania.”

The Commedia is an impressive work that took at least ten years to complete, and was finished just before Dante’s death. He takes examples from medieval art for the creation of his Inferno, including Giotto’s Last Judgment in the Scrovegni Chapel, and the depiction of the devil in Florence’s baptistery, which Dante saw as a young boy.

His journey through Hell is similar to a story of St. Paul’s journey, and that of Aeneas’s in the Underworld. Yet Dante crafts this in a completely unique way, combining pieces from ancient mythology and Christianity, all wrapped together in the beautiful rhyme scheme he created: terza rima(which follows an ABA / BCB format).

There is a reason Dante has survived for so many generations. There is a reason his poetry lives on and is studied today even by sixteen-year-olds in Kansas. We owe much of his legacy to Boccaccio, who, after his death, began a series of lectures in Florence on Dante’s work and ensured theCommedia’s survival. But we owe even more to the human imagination, to the innate fascination with the fantastical and the awe of genius. This is the reason the Commedia and the sources it drew on first came about, and this is the reason it lives on today. Humanity thrives on the power of the arts and of love—the only stronger feeling for Dante than hate—“that moves the sun and the other stars.”

Sources:

Quinones, Ricardo J. “Dante.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, 12 Oct. 2015. Web. 19 Mar. 2016.

Reynolds, Barbara. Dante: The Poet, the Political Thinker, the Man. Emeryville, CA: Shoemaker & Hoard, an Imprint of Avalon Pub. Group, 2006. Print.

Image of the dark wood at the beginning of Inferno (by Gustave Doré, 1861)

Image of devil in Florence baptistery (by Coppo di Marcovaldo, 1225)

Alex Wendt,

Liberal Arts Student (from Wooster)